The Opposite of Videodrome

Most Artists and Influencers Have a Philosophy. That’s What Makes Them Vulnerable.

Nothing in media is making money. Nothing. It’s gotten to the point where, according to this penetrating Slate article, most professional creatives are practically volunteers. It goes on to draw an illuminating parallel between most Hollywood actors on hit shows and influencers:

[I]f a whole hell of a lot of fans are unpaid creatives, it’s worth asking how many creatives are just fans who’ve gotten paid…After all, as striking SAG-AFTRA artists have demonstrated by disclosing their residuals (or lack thereof), a rather shocking number of writers, actors, and essential cultural workers look a lot more like volunteers than many of us likely imagined…But how many artists actually can support themselves by making art, rather than by family wealth or subsidizing their craft with other jobs? There may never have been a time when “artist” was a secure way to make a living; there may also have never been a time when it was worse than it is now.

Beyond low pay, most creatives are willing to work for free.

After all, what makes arts and culture different from most industries—and what makes these distinctions tricky—is that its workers will and do work for free. They’ll hold down a job as a waiter or a package handler or sex worker, all the while going on auditions or working on their poems at night. They’ll struggle through open mics, work for exposure, and display their paintings gratis. They’ll do what they have to do to survive—while making pennies on their actual art—because they want the job more than the job wants them, because money makes it possible to do the job, rather than the reverse. A variety of feminized care professions get paid less than they deserve, when they care too much for their clients to leave the profession, but even an elementary school teacher who might be buying supplies for their kids out of their own pocket—allowing the district to keep property taxes splendiferously low—won’t actually hold down a classroom without pay. But making art for free is so common and normal that it’s just “paying your dues.”

How did we get here? Why do creatives debase themselves more than sex workers? Has it always been like this? Yes and no. For centuries, artists worked for church and state. Fair labor wasn’t even a concept. When the Industrial Revolution dawned, creatives rebelled because now the market had them serve the bourgeois marketplace instead of answering to a loftier authority. Many artists like Baudelaire and Rimbaud became bohemians, willing to starve for their hashish-fueled visions as opposed to whoring themselves in the marketplace. 1

Charles Baudelaire

For almost two entire centuries, this was the credo artists the world over followed. Not serving church or state anymore, now it was noble to suffer for your vision, or to put it less romantically, your philosophy. Your world view. A little more than a hundred years later, in the ‘50s, with the independent press chapbook revolution, in addition to the Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway movement, this dream of working outside of major capitalism could be a reality. This dream was the beginning of the indie revolution that spread everywhere over the 20th and 21st century, from music to video games. This escape from Big Business was not flawless. Most mom and pop shops also exploited creatives, often delaying pay for months. The indie darlings that had enough attention were hoovered up by major corporations that would astroturf them by signing them to smaller, subsidiary, vanity imprints.

An important facet of the indie world that is important to look at is the DIY ethos which again came from the 1950s literary and theater world. Before the ‘50s, some sort of patronage was an assumption. Even French 19th century bohemians needed major publishers to validate them. The very concept of making something and showing it to the world without major gatekeepers did not exist outside the world of crafts or baking. The elation and excitement of this made issues like pay seem borderline irrelevant.

Then along came the ‘90s, with its cyber-utopian promise of digital culture taking down the gatekeepers. As late as 2009, with blogs still being semi-relevant, that dream was still alive. In the 2010s, we saw that the gatekeepers moved from Hollywood and New York to Silicon Valley. Social media helped centralize the web. The idea of selling out was obsolete, quaint. Before 2010, selling out meant a contract with Paramount or Geffen . Nowadays, corporate creative work is a glorified gig economy, especially for influencers.

Moreover, with social media like X, Instagram and TikTok being deemed a necessity for every creative alive, it is impossible for any creative to even play-act that they are living outside of capitalism anymore. The bohemian dream ended with a rude awakening. Ten years after that rude awakening, it turns out that patronage itself is hardly an option. In case you forgot, nothing in media is making money. Nothing.

Despite the rude awakening, many creatives work as if the bohemian dream is a reality. Influencers and screenwriters continue to debase themselves to push their philosophy. And it is this very commitment to their guiding philosophies that is blinding them. Corporations would kill to have their employees follow their company philosophy with as much zeal as an artist follows their own guiding beliefs. It may suck to work for Starbucks, but Starbucks workers, union or non-union, are less likely to put up with labor abuse. Artists, forever serving their muse, are blind to what’s behind the curtain.

Right! That’s why my movie about the evils of capitalism sets me apart from the pack.

Nope. Many young Millennials and Zoomers are socialists, or at least skeptical of capitalism. You see a movement. Apple TV + and Netflix sees a market. A show that skewers capitalism doesn’t hurt capitalism anymore than a ‘70s sitcom denouncing white racism against blacks hurt the white writers or executives that profited from it. This is actually the greatest paradox of all: the message of Marxism blinds the writers and actors to their exploitation or makes them complicit in their own exploitation to get the message out.

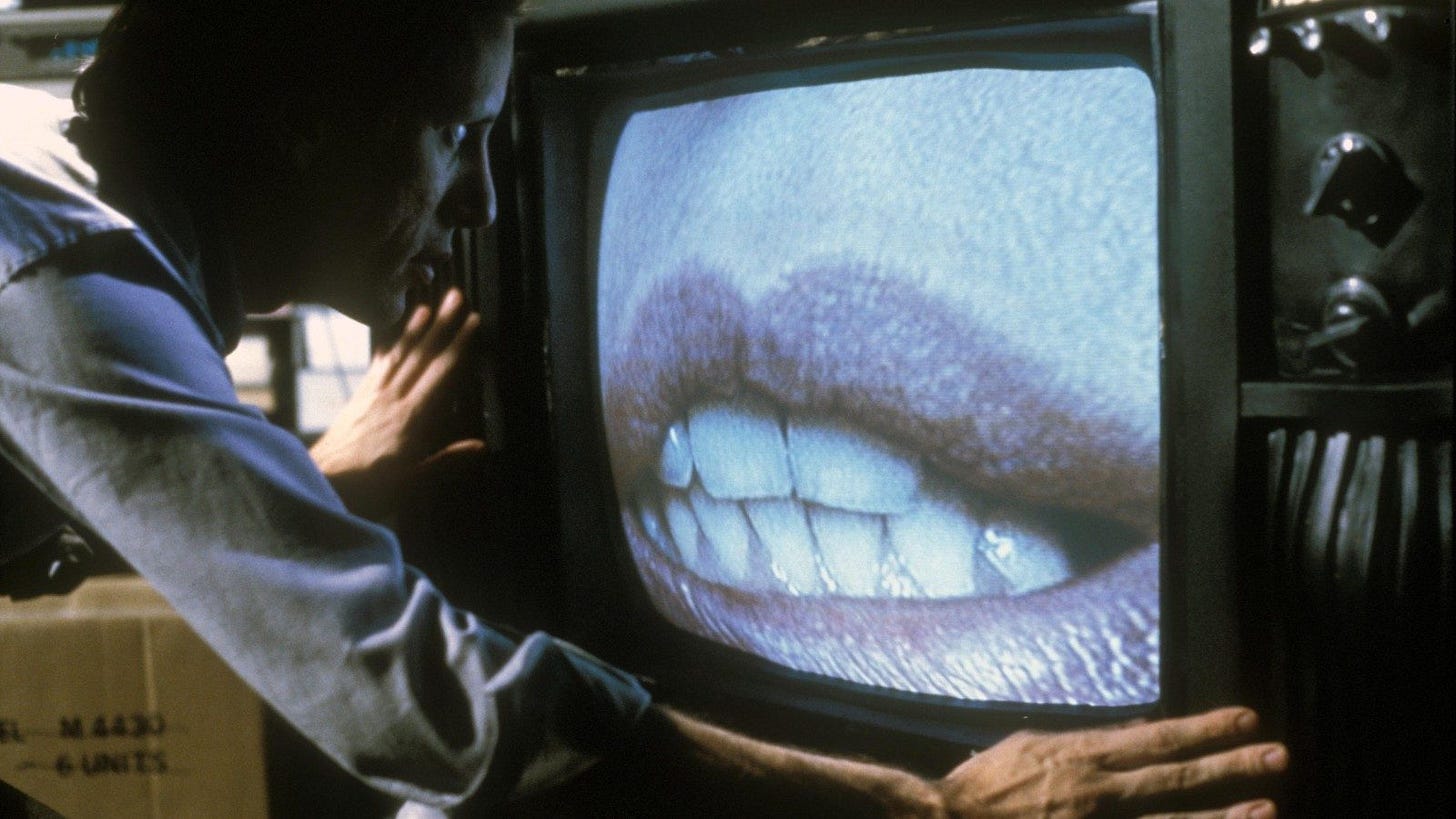

A famous quote that I always loved from the brutally brilliant 1983 sci-fi classic Videodrome about a disturbing video the movie centers around:“It has a philosophy. And that is what makes it dangerous.” The opposite is true about today’s creatives. Today’s creatives are blinded by their vision, forever forced to either live on meager pay or else be unpaid, overworked amateurs with soul-sucking day jobs, for the cause.

And it’s not just creatives. In order to compete with influencers, who are the most trusted news source for today’s youth, more journalists are being forced to make personality driven TikToks:

The Los Angeles Times…[are] one of many publications attempting to recreate the success of individual creators on TikTok within their newsroom. The Washington Post’s account shot to fame in 2019 thanks to host Dave Jorgenson’s irreverent reimaginations of the news and has since earned over 1.6 million followers and added a handful of additional hosts, including Carmella Boykin and, most recently, Chris Chang. Chafe as legacy media might, Gen Z is giving them no choice but to adapt — or get lost in the algorithm

The journalists no doubt believe that if they don’t do a skit on global warming with a computer-generated fishing boat, democracy dies in the darkness.

The SAG-AFTRA/WGA strike is all about how corporations should not give their work to AI. Deep down, I am actually starting to wonder if the studios really are so dumb as to not keep exploiting people instead of machines. If they displace people, then they will have created a whole population with a philosophy, but without jobs. And that, now that, is volatile, unstable and dangerous. Or, to paraphrase a greatly misunderstood proto-rap song, the revolution will not be streamed.

I learned all this in a great book called The Village: 400 Years of Beats and Bohemians, Radicals and Rogues, a History of Greenwich Village by John Strausbaugh

The worst part of it all is how creatives have been trained to believe that making money from their work somehow debases it.