UPDATE: I WROTE THIS BEFORE REALIZING THIS WHOLE DARK AGE THING IS A HUGE CONCEPT ONLINE EVEN WITH ITS OWN BOOK. PLEASE GOOGLE IT. I WISH I DID. ANYWAY LEAVING IT UP BECAUSE I AM WILLING TO BET NO ONE IS SUGGESTING THE GIRARDIAN SOLUTION I PROPOSE.

About a month ago, I mentioned how Elon Musk taking over Twitter was the end of the social media chapter. More and more articles surfaced saying that this might be the end of social media. These are the best of those.

But something else I mentioned in my next post seems to be echoed by nobody.

Now quite a few writers have mentioned the importance of making backups so your writing does not get lost. But this seems cope if only because an obvious question isn’t being raised, let alone answered: what happens when Elon Musk wants to profit off your published book of archived tweets?

When a writer is worried about their work getting lost, surely they are not worried about it literally being lost so even they can’t read it themselves. This is a question of posterity, legacy. They want to cull the best tweets and publish them so their lifespan is increased tenfold. I find it hard to believe that Elon Musk won’t want a cut of that money, forcing many liberal journalists to reluctantly leave it on the site, hoping that Twitter doesn’t go the way of the blogosphere.

As I also mentioned in the post linked to in the block quote above, the blogosphere’s demise was a mass extinction event that happened so quickly, people practically forgot its existence. As it stands now, Twitter is primarily a party of legacy media creators from the most decorated journalists to the most vapid celebrities. For this reason, journalists feel an acute pain from all this that Joe Paycheck cannot relate to, but can mock effortlessly. Don’t be surprised if Twitter’s actual 404 demise is met with an even more caustic shrug.

I myself have never been a hit at the Twitter party or even that much of a reveler. But I do like Substack and, having said that, I am not entirely sure that Substack isn’t also by media personalities for media personalities. But this is all moot. Vine, a video app that people of all ages and races liked, died quicker than Twitter ever did. And way more unceremoniously.

So what does this mean, when an entire style of publishing has at best a decade lifespan? Before new media, when a song was outdated, it didn’t mean you couldn’t hear it anymore. It just meant you couldn’t hear it on the radio as much. The disco songs that were mild enough survived by escaping from top 40 and staying in the shelter of lite FM limbo.

Unsurprisingly, many Internet creators are moving to legacy media to survive. The fringe writers are either going to small publishing houses or are self-publishing books, even magazines. But some of these creators may be enough on the cusp of mainstream respectability to enter Hollywood.

This is an understandably unpopular question but I can’t put it off any longer: is part of the reason why these media spaces come and go so easily because there is nothing in them worth preserving? This may scan as an elitist question, but it makes more sense when compared to Hollywood.

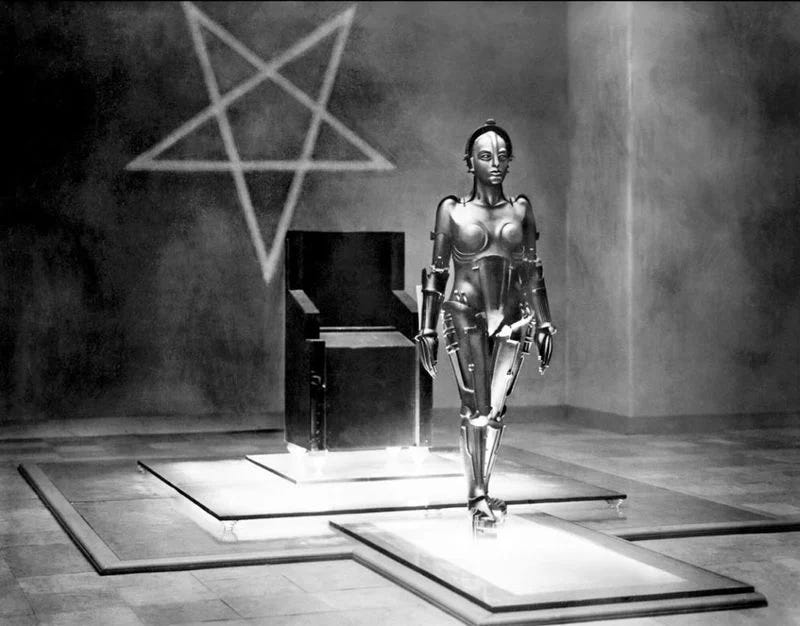

Metropolis, 1927

Before the 1920s, movies were the Cinema of Attractions. Films were one reelers with slapstick, cute/acrobatic animals, wondrous visuals of exotic locales. Sound familiar? It should. This is making a Chinese networked media app very rich right now. But at the time, very few people had any idea that film would grow in narrative and linguistic complexity, thanks to sound. But eventually the Golden Age came. To put a finer point on it, cinema was introduced in 1895 but did not even hint at its Golden Age until the ‘20s.

I find this parallel particularly fascinating because the world wide web was introduced to the public commercially in 1995. And right now we are in the ‘20s. As many Tweeters blame Musk for the end of Twitter, a few, more self-examining writers may ask “What did I write that was worth preserving?” As Owen Heatherly points out in Jacobin:

A lot of blog writing was dreadful, but it all involved effort, actually writing at moderate length and trying to be coherent and cogent. Posting was easy, and it didn’t need to make sense — over time it was clear that Twitter was better if the tweets didn’t quite make sense, which is why the essence of the medium is and always will be Dril……As Elon Musk destroys or bankrupts Twitter or transforms it into a more comprehensively monetized version of 4Chan, it’ll be easiest to recall all the awful things about it — its self-righteousness, its torrents of racist abuse, its incessant, grotesquely pious intragroup policing, all those insufferable “y’all need to know” buckle-up threads, the eggman accounts patronizingly telling you things you already know, the intensification of false or exaggerated claims, the bite-size threads of poor history, and the straightforward obnoxiousness. Crucially, its owners recognized the importance of these over time in drawing people again and again to the site, creating algorithms that intensified all of this cruelty. Posting is amoral, and any regular on Twitter will recognize just a little of themselves in the bizarre, splenetic word salad of Donald Trump’s tweets (and he was truly a master of the form).

Meanwhile, the best writer to come out of blogging is Mark Fisher. Perhaps because he owned his own domain, etc., his writing and legacy are better preserved. Which is certainly a wise idea. But can it be denied that his writing was actually worth preserving? His suicide may have boosted his acclaim, but many TikTok stars died this year and they do not seem to have made a similar impact.

Is part of the reason why these media spaces come and go so easily because there is nothing in them worth preserving?

How could they? They were so young. It may very well be social media/networked media’s status as a youth hangout that is making it relatively unworthy of preservation.

For much of human history, storytelling was the exclusive privilege of designated elders, bookish scholars, and ambitious artists. To create motion pictures, aspiring filmmakers had to pay their dues at schools and in the industry before getting their hands on a camera. The internet opened storytelling to everyone, a development long beheld as a great democratic revolution. But this also has robbed nerds of their longtime monopoly on content creation and gatekeeping. When everyone is making content, teens have extended the high school hierarchy into their viewing habits: Why watch the weirdos when the cool girls are showing off their shopping hauls and class clowns are embarrassing their bros in epic pranks? Thus the very appeal of TikTok is its “mediocrity,” writes Vox’s Rebecca Jennings: “No one follows you because they expect you to be talented. They follow you because they like you.” Previous generations of lowbrow Americans may have enjoyed passive consumption of Candid Camera and America’s Funniest Home Videos, but Gen Z’s analogous content is defining their generation the way the Beatles defined the baby boomers and MTV defined Gen X.

Funny how he mentions how The Beatles defined the Boomers. The Beatles were the ideal teeny bopper band. Girls loved their fashion and good looks. Boys loved their laddish humor. It wasn’t until they met Bob Dylan that they smoked dope, got weird and became artists. Had it not been for Bob Dylan, it is very easy to imagine how rock would have been a strictly dance-oriented fad with zero literary or artistic merit. Well, not beyond a trash culture sense anyway. The ‘60s would have had no Jefferson Airplane but plenty more Trashmen songs. The ‘70s would have had no Patti Smith but way more KISS clones.

Rene Girard has been elevated as a thinker thanks to many of his ideas on mimesis proving true on social media. All it would take is one Bob Dylan figure in New Media to inspire countless imitators and help make the Internet something worth preserving.

Tempting as it may be to end on this very hopeful note, especially on a major holiday weekend, I would be remiss if I didn’t look at the conditions that gave us classic Hollywood and Bob Dylan. In ‘20s Hollywood and ‘60s New York, the barrier to entry was high. You needed to have some talent. Or, to put it another way, Hollywood and Columbia records were not making money on hopeful showbiz losers. Social media sites like Twitter are full of celebrities and award winning writers, but they are actually powered by losers that have enough retweets and likes to delude them into thinking that they may crack open the attention jackpot and get a book deal.

This is one hindrance that may prolong and deepen the Dark Ages of New Media. Social media itself might have numbered days, but the algorithmic business model that powers it will slither from host to host as if it is learning its dance from the ‘80s cult sci-fi horror classic The Hidden.

The Hidden, 1987

In ‘20s Hollywood and ‘60s New York, the barrier to entry was high. You needed to have some talent. Or, to put it another way, Hollywood and Columbia records were not making money on hopeful showbiz losers.

From the latest issue of Spike written by Rob Horning:

The more compelling and fascinating a post is, the less disposable it is. Algorithm-based apps like Twitter and TikTok thrive because their user base always wants to know what is next. I am convinced that the pleasure of TikTok has less to do with the visual pleasure of the videos themselves or even the catchy tunes we hear. It is all about the tactile pleasure of swiping up mindlessly.

I do see a pin-sized glimmer of light though. And it involves another social media site that I never really got into: Tumblr. Many Twitter refugees on Tumblr were invited to participate in their first Tumblr prank. This time, it is a fictional Scorcese movie called Goncharov. On the surface this is a mindless Internet thingie. But I think the forces of hyperstition are too strong here. This seems to be symptomatic of an Internet that is increasingly tired of MCU potboilers in theaters and on TV.

But I also think many of these creators want to create something as durable and meaningful as Scorcese’s works. We’ll see how far mimesis takes us here. But the mimesis of Greco-Roman antiquity did help launch the Renaissance.