The Real World debuted on MTV 30 years ago in 1992. To understand it’s impact, let’s look at what searching for fame was like in 1991. If you wanted to be famous (say, a country singer) you needed to play at local venues (either open mikes or pay-to-play, usually both). Once you had a legitimate following, you had head shots and a demo. If you succeeded, great. If not, you got the old “don’t call us we’ll call you” and it was your choice to either keep deluding yourself or quit. Either way, no one told you to keep making demos. There was no Gary Vee to tell you “don’t create, document.” Most important of all, the deal was, if Nashville wasn’t returning your calls, they weren’t making money off your song either.

Now let’s go to 1992. MTV suits come to a scary realization: the remote control is increasingly killing their business model. In 1981 (when MTV launched) most people who had it would get up to change the channel if they didn’t like it. Even if they had a remote control, the choices weren’t that great. By 1992, there were other music channels, let alone other channels. Oh, you didn’t want to hear Right Said Fred again? Who could blame you! Go to VH-1 or MuchMusic. MTV had no choice but to create original programming

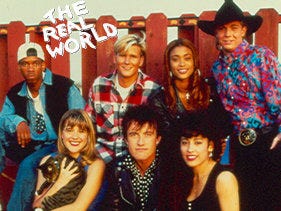

The plan: to make a soap opera of young, sexy twentysomethings. Two snags: MTV had to pay writers and actors. This was how programming worked before 1992. Except on MTV of course. MTV’s genius was having commercials (for Pepsi and Jordache) in between commercials (the music videos for Bon Jovi and Whitney Houston). That’s right: record labels paid MTV to play their videos. It made no sense to turn a revenue stream off. From this came the decision to make a reality soap with nonactors that got paid below scale and no script.

This led to one of the greatest revelations in capitalist history: it turns out, people do not only work for money. People love getting paid in attention. Especially young people. And for more than a decade, reality TV hopefuls loved getting paid in attention and a little money.

Then came social media. From 2003 on, the other shoe dropped. People love getting paid with attention even if they didn’t get any money. Even if you created the worst country song Nashville ever heard, if you posted it on Facebook. they were still making money off it, even if….especially if, you didn’t succeed.

The dirty secret of the attention economy is the same as that of casinos worldwide: they make money off you losing, not winning. Let’s take our country singer (call him Clint) and look at two parallel universes.

Universe 1: Clint is enormous on TikTok, He is Elvis-level famous. Chances are, since TikTok doesn’t pay creators too well, he might go to YouTube to expand his audience. As his audience expands, he will end up with a record deal, he will make the new James Bond theme. Short of it: all of that is time he is not spending on TikTok.

Record labels paid MTV to play their videos. It made no sense to turn a revenue stream off. From this came the decision to make a reality soap with nonactors that got paid below scale and no script. This led to one of the greatest revelations in capitalist history: it turns out, people do not only work for money. People love getting paid in attention. Especially young people.

Universe 2: Clint gets 40 likes on TikTok. OK that’s a start. He makes another video hoping for more likes. 45. Wow, his audience is growing. As time fritters away, he sees that not only does he not get more likes, most of his likes are from bots. He gets disillusioned and stops creating, This was the most likes he ever got, compared to all the other platforms, and it still wasn’t enough. So he watches TikTok as a viewer, mindlessly scrolling for funny videos to take his mind off the rejection. Maybe he even excitedly likes videos that mock TikTok (would there be a TikTok without anti-TikTok content?). One night he gets drunk, gets out the old guitar, and plays a song he doesn’t remember the next morning, when he gets suspended. He remembers now. It was racist. But he is suspended. Not banned. It’s not like this poor schmuck is Alex Jones. Look at that: he’s out of TikTok jail and he has a small, (40 likes small) but dedicated following of bitter, angry alcoholics that love his racist country songs. Not outwardly racist, mind you. Just jokey, edgy songs about, say, how The Little Mermaid is dark because he cooked her thinking she was a bass.

Universe 2 is TikTok’s goal of course. And TikTok owes it all to The Real World. Initially, MTV gave season one cast member Eric Nies a hosting gig for The Grind. A momentary lapse in judgement. They realized, just like in the ‘80s with music, that MTV wasn’t great because of the talent, but the talent was great because it was on MTV. Who had time for building the egos and paychecks of Real World cast members? On to different cities and different people (but the same age range: below 30).

(courtesy of Business Insider)

There is a light in the darkness though. Substack is recruiting Instagram influencers who are tired of their pathetic attempts to replicate TikTok. This will lead to more money for influencers and, possibly, better content. If all these people are creating cool stuff for free, imagine what you’d get if they got paid?

Random Links

Vulture article about how maximalist movies are fun and should continue being released in theaters. I disagree but I am confident that this Vulture writer will get their wish. In the ‘50s and ‘60s, when Hollywood was threatened by TV, the word around town was the bigger, the better. And that was when Hollywood only had one threat.

Web3 is giving fans more input into the creation process of their favorite properties. Part of me bristles at this idea, but best case scenario, this is like the folk movement of the ‘60s, when various singers played versions of old traditional classics. This is the world Bob Dylan came out of and we all know his impact.

Ion Pack podcast interviews CFCF. At one point, a discussion on how vaporwave devolved leads into an aside of how Instagram cellectual meme accounts lost their edge. After being taken aback by the snobbery, I felt weirdly nostalgic for hipster elitism and even got more excited that perhaps the indie sleaze comeback might lead to a return to the hyperelitism of the hipster 00s, when the Internet expanded everyone’s music knowledge base and made connoisseurs out of coffee shop cashiers. The difference this time being snobbery for content that is created online.

A deep dive into how the tech platform Urbit (created by neoreactionary Curtis Yarvin) is the very hub of downtown NY’s art revival. My $00.02: perhaps the biggest difference between entertainment and art is how much the former seems to rely on technological progress. A great example of an art form that ran counter to technological progress was indie rock. As postpunk synth warriors ran out of noise effects in the ‘80s, indie musicians pilfered the ‘60s for sunken treasures that didn’t get as much attention the first time (Red Krayola, even The Kinks’ later stuff). Twenty years later, vinyl was getting as huge, if not more huge, than digital. So you can keep your Web3, I’ll stick to my Web 2.5.