Typically, when this Substack looks to the past, it looks for cyclical patterns that might be relevant to today’s media landscape. This two-parter looks at a year whose spirit has never left us, for better or worse. Everything examined here will either prove to have never lost relevance or will only have been more relevant now than before.

Rebel Rock, Rebel Rap

The ‘60s will always have the most interesting, fascinating counterculture story. But, as any historian even more amateur than myself can tell you, interesting is not the same as important. Ever since the ‘80s, “counterculture” would be replaced by “alternative.” After the Iran-Contra affair, Reagan wasn’t necessarily the Teflon President everyone said he was. But mainstream culture still needed to put on its happy soft-power face, which meant more soft-core porn hair metal videos. More seat-rumbling action blockbusters. The more critical, the less cheerful, darker side of American culture needed to grow in the dark like mildew. Hence alternative culture and alternative rock. 1987 was the banner year of alternative rock (The Cure, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, R.E.M, Document, The Smiths, Strangeways, Here We Come, Sonic Youth, Sister, Pixies, Come On Pilgrim, Dinosaur Jr., You're Living All Over Me) but something was brewing in Seattle in 1989.

By that year, the Sub Pop record label was already an indie rock juggernaut and Mudhoney was the hottest grunge band in Seattle. When alt-rock critics got their hands on Nirvana’s debut album Bleach (also released on Sub Pop), though, some were saying it was even heavier than Mudhoney’s Sub Pop underground smash Superfuzz Bigmuff. One fan of the album — Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth. When he was recording Goo in 1990, he wanted that heavy Bleach sound. This led Moore to bring Nirvana to Geffen (the major label for their breakthrough album Nevermind) and bring them on tour in 1991.

1989 was such a cataclysmic year, it is better considered the first year of The Long ‘90s (1989-2000). As grunge was getting ready to explode and hair metal’s denim started to fade, hip-hop had its own revolution. As rap gathered momentum in the ‘80s, it got stranger, more psychedelic. Public Enemy’s 1988 masterpiece It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back had a dizzying flurry of samples. The Dust Brothers (producers of The Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique) and Prince Paul (producer of De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising) took notes. But their approaches on their respective 1989 masterpieces were less of an assault, more of a sampledelic delight, as if the listener took a journey into the murky subconscious of mass media: its forgotten pop songs, its soap commercials, its Saturday morning cartoons. The ‘60s was the golden age of psychedelia generally speaking, but these two albums recreate the psychedelic experience more than most albums have before or since. The dizzying giddiness of throwaway sonic gags and dime-store divinity fit in well with the surreal, rapid-fire comedy of The Simpsons on TV and the acid-house insanity that took over the UK in 1989.

But to truly understand 1989, you need to look less at its chart toppers or its seminal works and more at its controversies. And 1989 had its share. Exhibit A: 2 Live Crew, As Nasty as They Wanna Be. Rap (and rock) in the ‘80s had crass, offensive language to spare before 1989. But the understanding was that the hit single would be cleaner than an anorexic’s fridge and the album cuts could be as nasty as they want. “Me So Horny,” (a song which was offensive in 1989 for its offensive content and is arguably more offensive nowadays for its Asian objectifying sample of the Vietnamese prostitute from Full Metal Jacket) was a hit single in 1989, but it got no airplay. Initially, at least. By the time it hit the top 40, major metropolitan radio markets had no choice. A radio edit was released. The radio edit covering up the smuttiness as much as the bikinis on their album cover hid the sun-dappled flesh.

An obscenity trial followed in 1990. As romantic as it may be to say Nirvana or De La Soul were more influential, in our W.A.P. world, it is 2 Live Crew whom we must look to and give a firm-handed salute for breaking open the floodgates of expression. Floodgates that many to this day on the left and right want to repair.

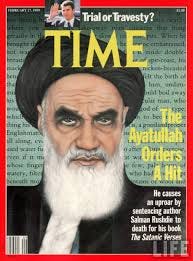

Fatwa

The best-selling book of 1989? Tom Clancy’s Clear and Present Danger. The 1989 Pulitzer Prize winner? Anne Tyler’s Breathing Lessons. But, then and now, those books do not have the impact of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. There may be better press out there than the leader of Iran ordering your execution for something you wrote, but I have yet to find out what it is.

The Satanic Verses is a magical realist novel about the immigrant experience in the UK. It has a few dream sequences, one of which is based on an apocryphal story about the Prophet Muhammad including verses in the Koran about three pagan Meccan goddesses and striking them from the record because he confused satanic influence with divine inspiration.

The book itself is less interesting than the controversy of course. Watching the news every day to see whether Rushdie would get caught was like a true-life perverted version of The Fugitive. The story ripped through social media last year, when Rushdie was stabbed by a would-be fatwa assassin (Rushdie survived). But 2022 was a different time. Criticism of Islamic fundamentalism was now right-coded. Leftists, especially Millennial leftists, did not condone the stabbing, but Rushdie was also not the hero he was in 1989. If this happened today, the expectation would still be for Rushdie to be protected physically, but also for him to have his book dropped from his publisher, so Muslims would understand that their feelings are valid (full disclosure: I am ethnically Muslim but am not religious and am marginally spiritual). In summation, he would be hunted and canceled.

The Birth of Modern Film

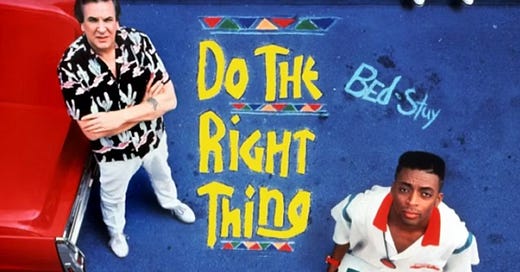

Right now, I can watch a big-budget comic book blockbuster (Guardians of the Galaxy, Volume 3), a film about life as a member of an ethnic minority in America directed by a member of that tribe (Joy Ride), or a buzzy, quirky independent film (Asteroid City). These were not choices you could take for granted in 1989. Batman, Do the Right Thing and Sex, Lies and Videotape walked so today’s films can run.

Batman is not only important as one of the first major comic book summer tentpoles. It also began the race for opening weekend box office receipts as well as narrowed the window between theatrical debut and video release. 1989 was an important year for better and worse. Batman began Hollywood’s love affair with movies that make money as quickly as possible at the box office so they can achieve enough buzz to get a similarly rapturous response when they are introduced into the home market. Great for big, splashy blockbusters. Not so much for intelligent Hollywood films made for adults that need some time for word of mouth. Because of Batman, sleeper films are an increasingly rare phenomenon.

Before 1989, non-white directors were a rare phenomenon. Films about black people, Asians, gays, were written and directed by white people, if not white men. And, of the few that were minority directed, none of them had an incendiary Public Enemy dance number that said fuck Elvis Presley and John Wayne, two white male conservative icons whose deaths a decade before helped usher in the Reagan era. Like The Satanic Verses and 2 Live Crew, Do the Right Thing was a lightning rod for controversy, many fearing that the riot Mookie incites in the film would incite actual riots in movie theaters. Though it didn’t, years later, Hollywood itself would grow increasingly diverse in response to the riots over Michael Brown and George Floyd. More films about minorities telling stories told by minorities. Also more brain-dead Hollywood blockbuster reboots starring minorities and sometimes even directed by them. Few of them having the courage of Spike Lee, unfortunately.

Few Hollywood films anyway. Remember: the ‘80s gave us an alternative culture, not a counterculture. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, the lunatics ran the asylum. From the late ‘80s on, the lunatics would have their own alternative community. Much like Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 marked the arrival of New Hollywood, Sex, Lies and Videotape established the golden age of indie film in the ‘90s. And to this day, it established the path to success for an indie film director: place in at least one indie film festival, have a breakthrough hit, make enough box office hits to make money and win enough leverage for personal projects without selling your soul completely. Steven Soderbergh learned this the hard way. After his debut Sex, Lies and Videotape won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, he released failed experiment after failed experiment until nine years later when the star-studded Universal Studios heist film Out of Sight saved him from movie jail. Though he would go on to create major Hollywood films like Erin Brokovich and Ocean’s Eleven (back when Hollywood films were not all based on comic books, toys or video games) he also had enough freedom for critically acclaimed passion projects like Bubble and High Flying Bird.

One last thing…

In 1989, CERN researchers were vexed at how hard it was to share information with each other. How were thousands of researchers all over the world supposed to read each other’s papers on particle physics? Libraries? Mail? Tim Berners-Lee proposed a method that would use a network of computers that used hypertext to share information with each other globally. What we now call the World Wide Web.

Insightful point about 1989 being the first year of the long Nineties, Mo. In a sense the long Nineties didn't truly end until America was blasted into the 21st Century on 9/11/2001.

Remember the Bush Tax cuts of early 2001? I actually received a check for $300. This was just George W Bush's way of keeping the '90s party going as well as distracting the people from the reality that he gained the presidency from a Supreme Court ruling.